The 1980 Moscow Olympics boycott led by the United States under President Jimmy Carter was a direct response to the Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan in December 1979. Over 60 countries joined the U.S. in refusing to participate, making it the largest Olympic boycott in history. The Soviet-led counter-boycott of the 1984 Los Angeles Games followed, but the 1980 action was driven by Cold War geopolitics, strong U.S. leadership, and broad Western alignment against a clear military aggression.

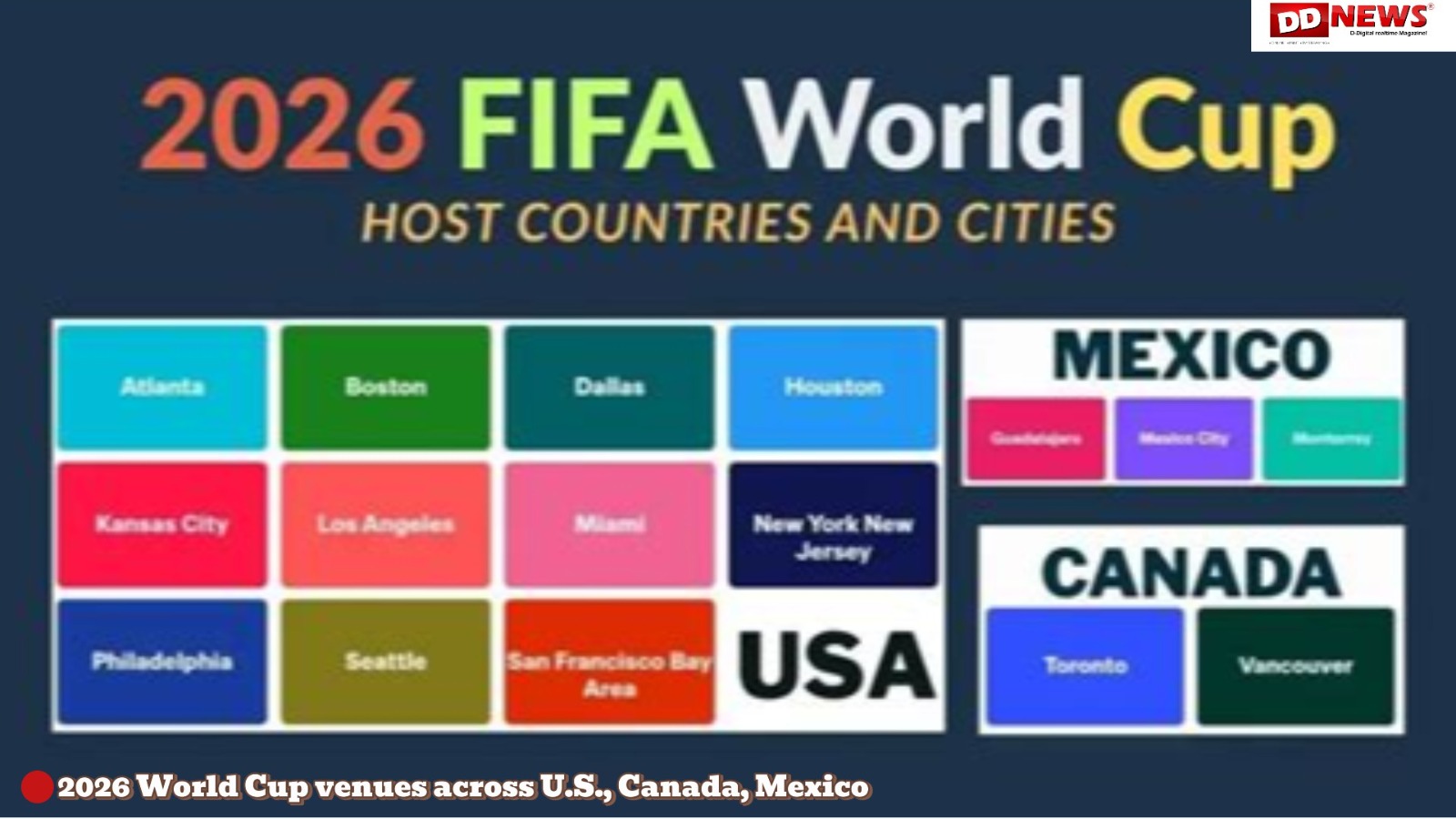

In contrast, the 2026 World Cup (co-hosted by the United States, Canada, and Mexico from June 11 to July 19) has seen some calls for boycotts or withdrawals, mostly from European voices, but these remain fringe, speculative, and unlikely to materialize into a meaningful, unified action. Here’s why a 1980-style repeat is improbable:

The 1980 boycott had a single, clear catalyst (Soviet invasion) and was orchestrated by the U.S. government with diplomatic pressure on allies.

Current discussions around 2026 stem from diffuse grievances: U.S. immigration enforcement (e.g., ICE incidents), threats over Greenland, travel restrictions on some qualifying nations, and general unease with U.S. policies under the Trump administration.

No major government (e.g., Germany, France, UK) has officially threatened withdrawal. Calls come from individual politicians (e.g., German MP Jürgen Hardt calling it a “last resort”), federation officials (e.g., German FA VP Oke Göttlich urging discussion), and former FIFA figures (e.g., Sepp Blatter supporting fan boycotts). These are opinions, not policy.

Subscribe To The Best Team In Conservative, Business, Technology, Lifestyle And Digital News Realtime! support@ddnewsonline.com

FIFA has invested billions and views 2026 as a massive commercial success (record ticket sales projected, global viewership expected in billions).

Co-hosts (USA, Canada, Mexico) are unlikely to self-sabotage. FIFA President Gianni Infantino has dismissed boycott talk as “noise.”

Unlike the IOC (which has less commercial power), FIFA controls qualification, scheduling, and revenue making coordinated withdrawal extremely difficult.

Massive financial & sporting costs: Withdrawing would forfeit qualification spots, prize money, sponsorships, and global exposure. Top teams (e.g., Germany, England, France) risk domestic backlash from fans and sponsors.

Fan vs. team boycott: Most current calls are for fans to stay away (e.g., petitions in the Netherlands with 140,000+ signatures, Sepp Blatter urging people not to travel to the U.S.). This might reduce attendance/revenue but won’t stop the tournament.

No broad alignment: European federations have discussed informally, but leaders (e.g., French FA president Philippe Diallo) have rejected boycotts. Polls show public support in some countries (e.g., ~47% in Germany under certain conditions), but not enough to force federation action.

Subscribe To The Best Team In Conservative, Business, Technology, Lifestyle And Digital News Realtime! support@ddnewsonline.com

Historical precedent shows boycotts rarely succeed: The 1980 boycott weakened the Moscow Games but didn’t end the Afghan war. The Soviet counter-boycott of 1984 was smaller and less impactful.

No national federation has withdrawn or threatened official boycott Calls remain speculative and from non-decision-makers (politicians, former officials, club presidents).

FIFA is proceeding full-steam: qualifiers are ongoing, venues are ready, and ticket sales are strong, analysts (e.g., in The Athletic, The Guardian, Washington Post) describe a full team boycott as “fanciful,” “unlikely,” and “extraordinarily low” probability.

In short: While political tensions and boycott chatter exist, nothing matches the scale, coordination, or government backing of 1980. The 2026 World Cup will almost certainly go ahead with full participation from qualified nations.

By Ogungbayi Beedee

Send tips to: adeyemi@ddnewsonline.com | 08168555497